Famintinana Ny fahatokisantena akory tsy midika ho fahaizana… iza amin’ny roa tonta no mahay-tena-mahay fa tsy bado-mihevi-tena-ho-mahay fotsiny? inona no zavatra mivaingana izay azo itarafana ny traikefa na fahaiza-mitantana ananany? iza no nahay nisintona lesona sy nanetry tena tamin’ny vita taloha ka sahy nanova famindra? iza no manome lanja ny fihavanana sy ny firaisankina ary tsy mampirisika ny fisaraham-bazana? iza no manana tetika na vina matotra sy azo tanterahina anatin’ny fotoana voafetra tsy nofinofy misavoandanitra fotsiny? –§– Mpanoratra Soamiely Andriamananjara sy Manitra A. Rakotoarisoa Efa betsaka ihany raha izay mpitondra nifanesy teto nandritry ny enimpolo taona latsaka kely naha-repoblika ity nosy mamintsika ity izay. Samy nilaza fa nanana vaha-olana ho an’i Madagasikara izy ireny. Samy nampanantena fivoarana sy fandrosoana faran’izay haingana sy maharitra. Harinkarena faobe an’i Madagasiakra 1950–2016 Hatramin’izao anefa, na iray aza dia tsy mbola nisy nahavita nanatsara ny farimpiainan’ny Malagasy mandritry ny fotoana maharitra. Isaky ny mba nisy masoandro nihiratra kely dia tonga foana ny sakoroka sy ny korontana ka rava ho azy izay mba saika tafajoro. Tsy mba nisy navela hahazo faka izay tsimo-pandrosoana nikelezan’aina sy nimatimatesana. Mazava loatra fa maro ny fanontaniana mipetraka: Fa tena tsy misy Malagasy mahay sy mahavita manaisotra antsika avy ato anatin’ny lavaka lalina misy antsika izao tokoa ve? Raha tsy misy izany, inona no fanantenana? Raha misy izany, maninona ary no toa tsy mba izy ireny fa olona tsy mahay na tsy mahavita azy foana no toa fidiantska hitondra ny tany sy ny fanjakana? Misy teoria tianay aroso izay mety afaka manampy antsika mamaly ireo fanontaniana ireo. Faran’izay tsotra ilay resaka. Isika angamba samy mahafantatra olona izay hita izao fa tsy mahay ny asany kanefa mbola mikiribiby milaza fa tena mahay ihany. Firifiry tokoa moa ny olona tsy mahafehy taranja iray mihitsy kanefa milaza azy ho manam-pahaizana na matihanina na expert amin’io taranja io. Misy amin’izy ireny no mpandainga na mpisandoka mari-pahaizana, fa tsy izy rehetra akory. Misy tokoa ny tena mihevitra ny tenany ho faran’izay sangany sy resy lahatra fa zokin’ny havànana na dia iaraha-mahita aza fa tsy dia mahay na zara raha mahay satria tsy azony an-tsaina mihitsy ny habetsaky ny zavatra tsy hainy. Arakaraky ny hakelin’ny fahaizanao tokoa matetika no hiheveranao fa betsaka ny zavatra fantatrao, ka mahatonga anao hieritreritra fa voafehinao tanteraka ilay taranja (kisary: miala avy eo afovoany dia miakandrefana). Ny fahatokisantena akory tsy midika ho fahaizana Etsy andaniny indray kosa dia arakaraky ny fitombon’ny fahaizanao matetika no mampazava aminao fa mbola betsaka ny zavatra tsy hainao sy hahaizanao ny fetran’ny fahalalanao. Rehefa mitombo ny fahaizana sy fahalalana dia mety mihena tokoa ny fahatokisan-tena (kisary: avy eo amin’ilay tendropika andrefana ka miantsinanana). Izay no mahatonga ny sasany amin’ ny olona mahay (satria nahita fianarana ambony ohatra na manana traikefa avo lenta) no tsy mba misehoseho izany fa toa mimpirimpirina ka heverin’ ny hafa ho bonaika na bado. Marihina kosa anefa fa raha mbola mitombo ihany ny fahaizana dia mety hiverina hiakatra indray ny fahatokisantena (kisary: avy eo afovoany no manohy miantsinanana) Mahagaga tokoa fa ny olona tsy tena mahay matetika dia mampiranty fahatokisantena be kokoa noho ny olona mahay. Ny bado mieritreritra ho mahay, ny mahay kosa mihevi-tena ho bado. Tranga tsy ampoizina loatra kanefa dia hita amin’ny lafimpiainana maro io paradokisa antsoina hoe Dunning-Kruger io. Raha misy olona maromaro ohatra mifaninana hahazo asa iray dia izay mahatoky tena indrindra amin’ny ankapobeny no mahazo ilay asa. Matetika anefa dia izy ireny koa no votsa indrindra amin’ireo mpitady asa. Torak’izany koa: ny mpanakanto tsy dia manantalenta fa mahatoky tena matetika no lasa misongadina na lasa ‘star’, fa ny tena tsara feo sy mahafehy mozika kosa dia misafidy ny zorombala hatrany. Afaka ampiharina mivantana eo amin’ny sehatra politika eto Madagasikara koa io lojika io hanazavana ny tsy fahombiazan’ireo fitondrana nifanesy teto: Ireo olona izay tsy dia mahay loatra no sahy miditra ho mpanao politika; ny mpanao politika tsy dia mahay loatra no lasa sahisahy hilatsaka ho fidiana amin’ny toerana ambony; ary ny kandida tsy dia mahay loatra no mampiseho fahatokisantena lavitry ny hambahamba ka manintona ny fon’ny mpifidy. Asa raha izany ny hoe mikobana fa feno tapany. Ny Malagasy moa voalaza fa olon’ny fo ka izay mambabo ny fony no fidiany fa tsy izay lanin’ ny sainy. Ny tena fahaizan’ny kandida tsirairay rahateo moa tsy hita eo no ho eo ary tsy ho voatsara raha tsy efa aorian’ny fifidianana fa ny fahatokisantena no hita sy tsapan’ny mpifidy. Dia iny no entiny hanaovana ny safidiny. Mety ho sarotra amin’ny mpifidy arak’izany ny manavaka ny kandida tena-mahay-ka-mahatoky-tena (kisary: tendropika atsinanana) amin’ny kandida tsy-alehany-kanefa-mahatoky-tena (kisary: tendropika andrefana). Resy lahatra tanteraka izahay fa be dia be ny olona hendry sy manana ny fahaizana sy ny traikefa ilaina hampandrosoana an’i Madagasikara. Saingy betsaka amin’ireny no tsy sahy “manao politika” satria mihevitra fa tsy voafehiny tsara io taranja io ka aleony manaja tena. Ary na manao politika aza izy dia mety miambakavaka sy votsavotsa firesaka satria tsy tena matoky tena ka tsy lasa lavitra loatra. Dia mety ho aleon’ny olompirenena mifidy ny kandida manao belazao mivarotra nofy fa mampiseho fahatokisantena (kisary: tendropika andrefana) toa izay hifidy olona mimpirimpirina sy mihambahamba (kisary: ampovoany) Dia izay angamba no mahatonga ilay hoe tsy izay tena mety hahavita azy no tonga eo amin’ny fitondrana fa olona manandrakandrana sady tsy dia mahay foana. Teoria ihany io fa tsy fantatra ny fahamarinany. Fa raha marina io dia tsy mahagaga raha olona be resaka fa tsy hahavita n’inon’inona foana no ho lany hitondra an’i Madagasikara na hifidy impolokely eo aza isika. . . . Ho avy izao ny fihodinana faharoa amin’ ny fifidianana filohampirenena ary efa tondraka sahady ny bala rora sy ny kobaka am-bava. Kandida roalahy mianaka no hisafidianana ary samy mihevitra ny tenany ho mahay mitantana sy maranintsaina na ny andaniny na ny ankilany. Samy milaza fa katraka ary manana ny fanalahidin’ny fampandrosoana sy ny ady amin’ny fahantrana. Samy mampiseho fahatokisantena tsy manampahataperana ireo kandida ireo. Izany fahatokisantena izany akory tsy voatery midika fahaizana mitantana ny raharaham-pirenena. Ka eo indrindra isika izao:

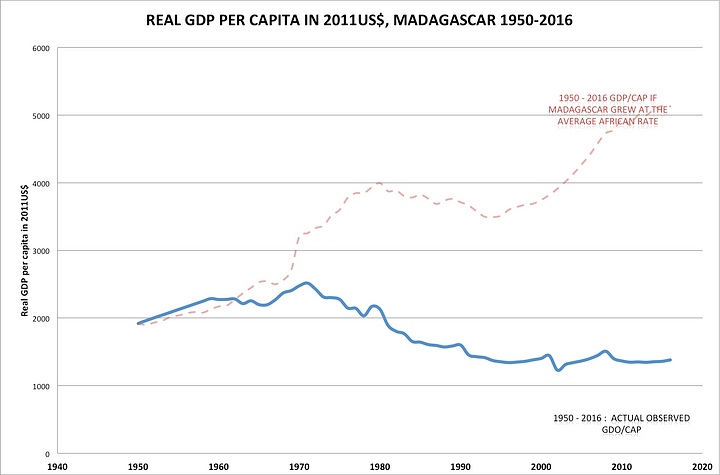

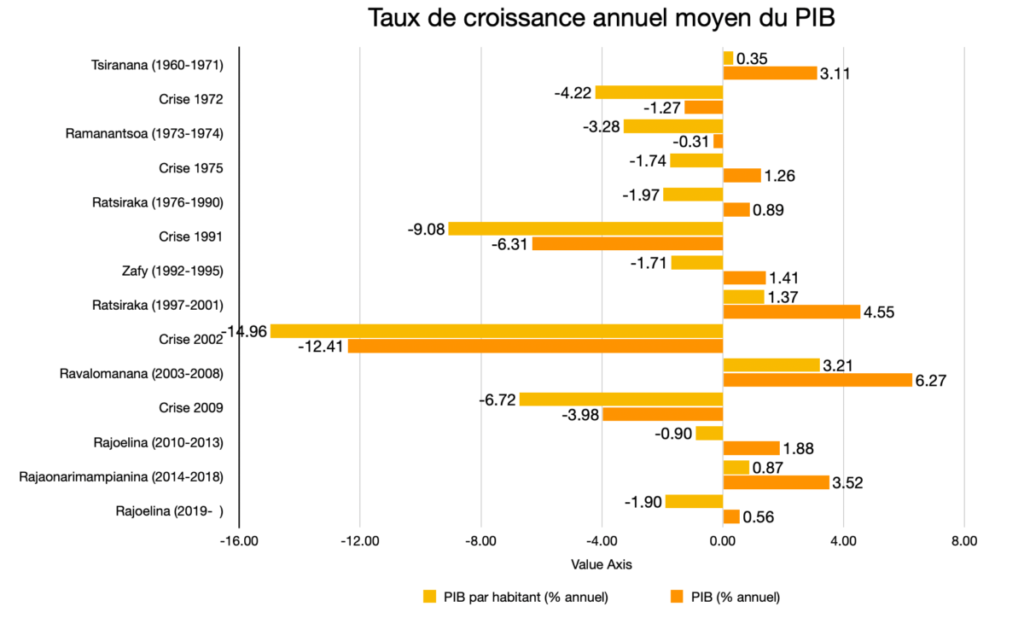

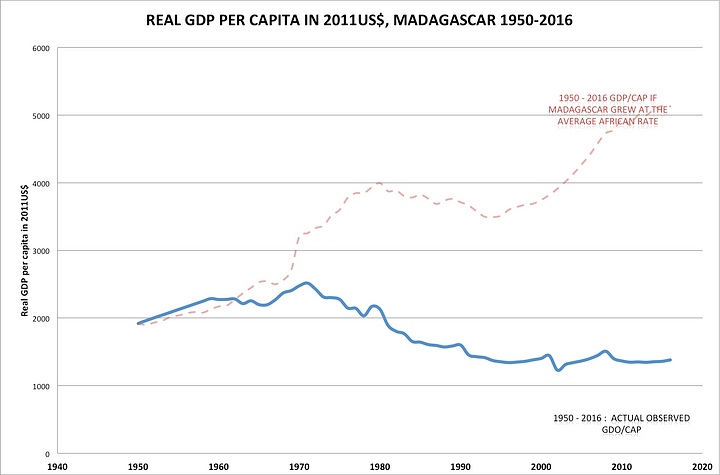

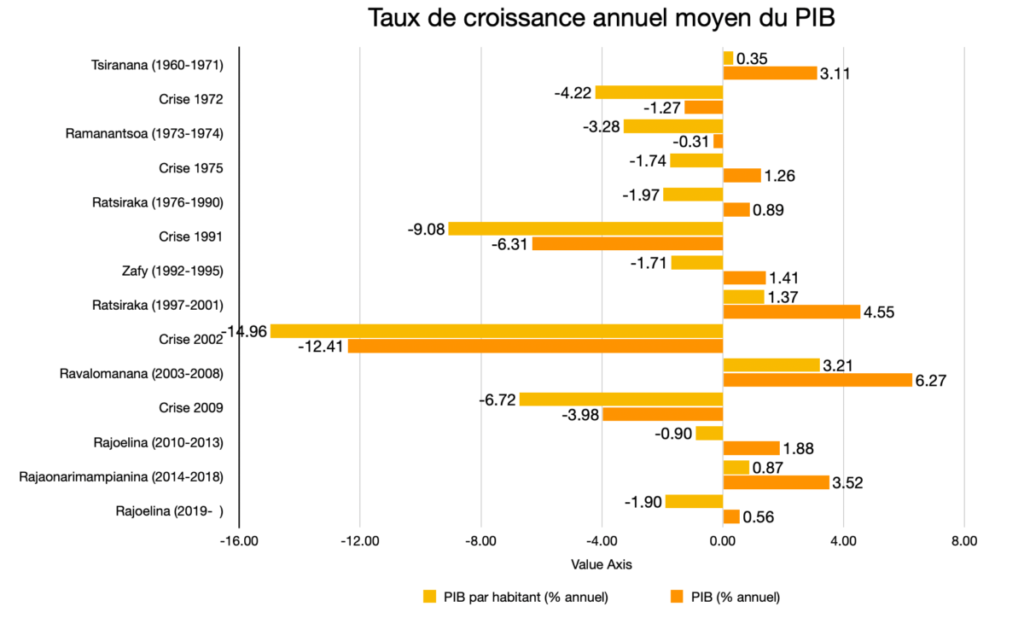

Abstract In this article, the author compares Madagascar to a child who, over the years, grows and develops as best he can. The figures are there to mark the stages of country growth with accelerations, bumps and regressions. The analysis stops at the 53rd year and the graph below brings us back to a « photo » of this evolution, up to 2019. It’s up to everyone to bring their own reading, but the facts are there and sometimes hurt the eyes. –§– Written by Soamiely Andriamananjara It’s All Part of Growing Up Raha zaza no tsy homam-bomanga, mitomboa ho lasa kilonga; Raha kilonga no tsy hitabataba, mandehana miala sakana; Raha miala sakana ka tsy hitraotra, milatsaha haingana ho vatombatony; Raha vatombatony no tsy hikorana, misondrota mba ho herotrerony; Raha herotrerony no tsy hisarizoro, mijoroa ho olon-dehibe; Raha olon-dehibe no tsy hitebiteby, mipetraha ho zoki-olona; Raha zoki-olona no tsy hananatranatra, mivadiha ho isan’ny antitra; Raha antitra tsy hitafasiry, modia ho lasan-ko razana; Raha razana ka tsy hitahy, mifohaza hiady vomanga! Our Malagasy ancestors (as well as psychologists like Sigmund Freud or Erik Erikson) have long understood that to live an emotionally fulfilling life, an individual has to go through a series of social stages. Each stage is characterized by a specific set of challenges, some of which can trigger stressful tensions and sometimes serious crises. If left unresolved, those crises can reappear with a vengeance at later stages of life. Just like an individual, a country needs to go through a sequence of stages before it fully blossoms into a mature nation — into a great nation. Let us consider the case of Madagascar which has been through several costly political crises over the last 55 years. Observing those crises from a psycho-social angle may seem simplistic and futile, but it is an interesting exercise and can provide useful insights, especially given that most of Madagascar’s problems seems to be driven by a certain lack of maturity. “Born” on June 26, 1960, the Malagasy Republic had a relatively nice and sheltered childhood. Although it was officially an independent nation, France was still very much involved in most dimensions of its life. The Reny Malala (beloved mother) continued to control large parts of the Malagasy economy and to influence all major policy decisions. Madagascar encountered its first post-independence identity crisis in 1972. Like most twelve year old pre-adolescents, it had a strong desire for freedom and autonomy. Malagasy people demanded more independence and challenged any form of imperialism. After widespread protests and revolts — which set the economy back by US$87 million — President Tsiranana resigned from office, General Ramanantsoa took over, and ties with France were scaled down. Computed using data from http://databank.worldbank.org The next crisis occured in 1975. The republic was almost sixteen — an age when confused teenagers become preoccupied with existential questions like “Who am I?” and “What can I be?” For Madagascar, this was a period of self discovery, triggering violent confrontations between different ideological camps. By the end of this transformative identity crisis, General Ramanantsoa stepped down, Colonel Ratsimandrava was assassinated, Commander Ratsiraka took over as the Nation’s leader. This crisis costed US$103 million, but a sense of national identity and common destiny emerged from it: The republic adopted a new name (the “Democratic Republic of Madagascar”) and followed a socialist ideology which would affect the country’s prospects for many years to come. In 1991, the Republic was 31 year old. This is the age for young adults to make important decisions regarding long-term commitments (“Should I get married?” “Should I marry my girl/boyfriend?” or “Should I start to have babies?”). By then, President Ratsiraka had been in power for more than sixteen years. This longevity caused anxiety, and eventually an intimacy or commitment crisis: Should we stick to this guy? Can we do better than him?Intensive soul-searching, accompanied by lengthy general strikes and protests costing the economy US$239 million, ultimately led to a regime change: Ratsiraka was voted out of office and Professor Zafy became president. In 2002, the Republic was about to turn 43 — the middle of the adulthood stage for an individual. Someone in that stage often insecurely asks himself: “Can I Make My Life Count?” and “Can I make a difference?” Madagascar had nothing much to show for in terms of accomplishment: GDP per capita was almost half of that of 1960. In an ironic twist of fate, President Ratsiraka was back in charge now after President Zafy got impeached. Though nowhere near its midlife, Madagascar was showing the typical symptoms of a mid-life crisis: people grew increasingly frustrated, stressed and impatient to achieve something meaningful. This impatience was personified by Marc Ravalomanana, a successful businessman known for his fast-pace no-nonsense take-no-prisoner management style. After a lengthy post-electoral standoff that set the economy back a whopping US$605 million, President Ratsiraka was once again kicked out of office, exiled himself in France, and Ravalomanana became president. The Republic was almost 50 in 2009— a symbolic age when most adults take s stock of their lives, sometimes experiencing frustation or depression because of unrealized goals or unsatisfactory achievements. The realization that “Madagascar has been independent for half a century and it was still among the world’s poorest economies” triggered a second mid-life crisis. In its haste to produce concrete results, the Ravalomanana regime made a number of serious governance faux-pas, which were quickly capitalized by a group of disgruntled politicians, led by the young mayor of Antananarivo, Andry Rajoelina. This opened the door for them to take over: After violent street protests, President Ravalomanana fled to South Africa and Rajoelina was made head of state. For the year 2009, the political turmoil costed US$242 million —Madagascar was subsequently subject to international sanctions and remained isolated until 2014 when Hery Rajaonarimampianina was elected president. Between 1960 and 2013, Madagascar went through five serious political crises costing an estimated total of US$1.3 billion, a significant chunk of its US$10 billion economy. One reason for the unusually high frequency and costs of the crises is the winner-takes-all attitude of Malagasy polititians, which raises the stakes and causes extreme behaviors and intense bitterness among those that are left out. Another reason